Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, occurs on the 10th day of Tishri, 10 days after Rosh Hashannah. Jewish tradition believes that on this day God places a seal upon the Divine decrees affecting each person for the coming year. In other words, decisions of life and death, peace and prosperity have all been decided and are now sealed. The Book of Life is closing on this day. Referred to as the “Sabbath of Sabbaths,” Yom Kippur holds a crucial place on the Jewish calendar.

Yom Kippur is mentioned in the Torah and described as a day upon which we are to “afflict our souls.” This phrase has been interpreted by the rabbis to include prohibitions against eating, drinking, bathing, wearing leather shoes and sexual cohabitation. It is one of the major fasts in Judaism, meaning it begins at sundown and continues to the following sundown. The Torah specifically connects the concept of atonement with this day and that connection has remained central.

The idea of atonement includes accepting responsibility for our actions through prayers of confession. These prayers mention both individual and communal sins and make up a large portion of the prayer services on Yom Kippur. The evening begins with the prayer of Kol Nidre, which absolves the individual of unfulfilled personal vows between the individual and God for the coming year. Its haunting melody marks the start of the fast and sets the tone for the next 24 hours.

Although Yom Kippur addresses both individual and communal sins, it is not a vehicle through which one corrects an injustice between individuals. There are two distinct relationships in Judaism: person to person and person to God. To atone for deeds committed against another person, Jewish tradition teaches, you must confront that person directly and apologize. Yom Kippur will address the impact that deed had on your relationship with God, but without the personal apology, the deed remains uncorrected. This element of the day often leads to difficult self-assessments and personal accountability for the choices made in the previous year.

Once the attempt has been made to confront and repent for misdeeds, the individual presents his or her “case” before God. The act of atonement makes the claim that as human beings we are able to change and improve ourselves. Thus we ask for one more year in which to continue this journey of change and improvement. We do not make the case to God that we are deserving of another year or deserving of blessings, rather that although we are undeserving (as our confessional prayers have pointed out), we contain within us the potential for righteousness and need time to actualize this potential.

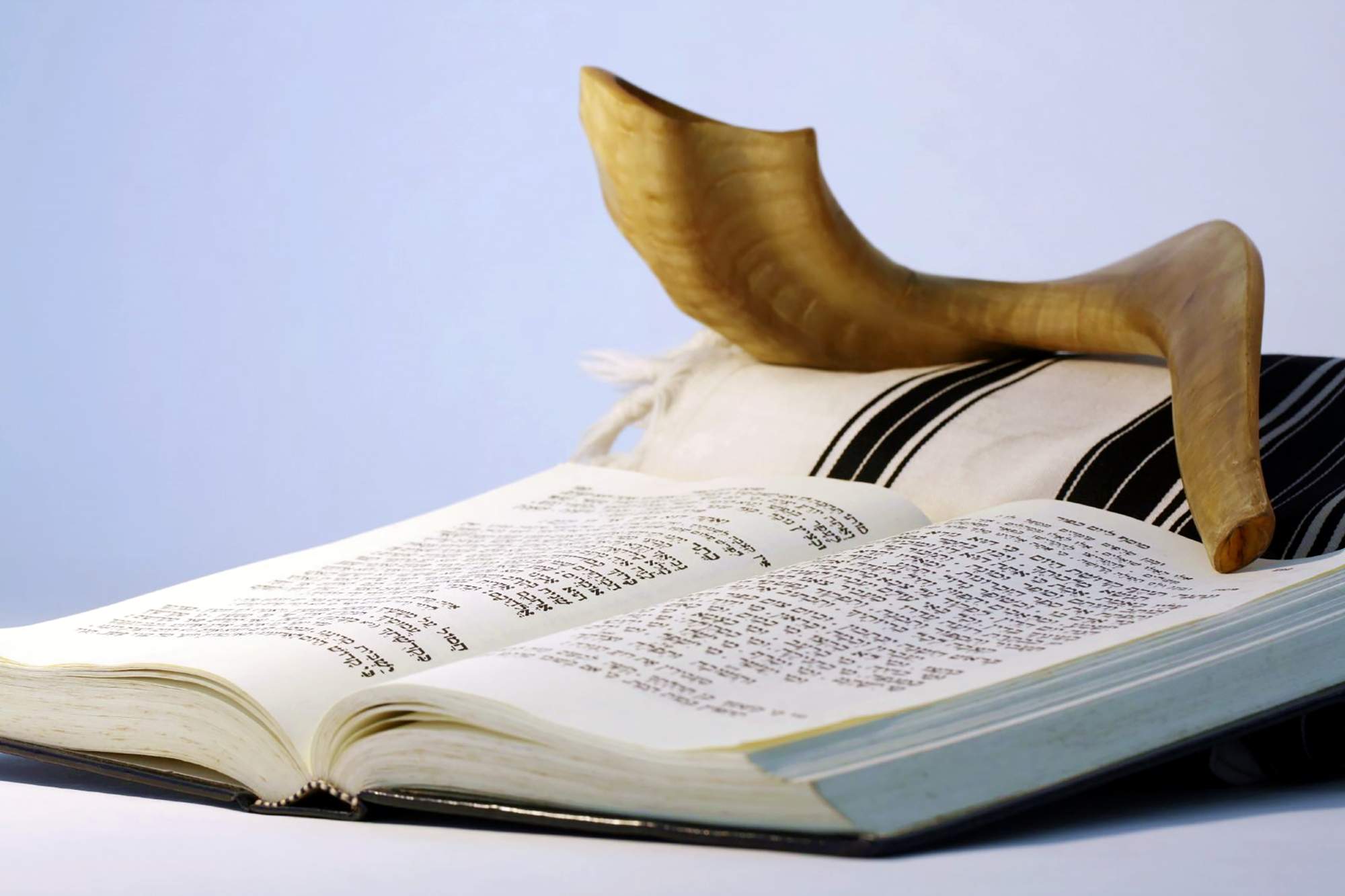

Throughout the period of Rosh Hashannah and Yom Kippur, the shofar is blown regularly. The shofar and its sounds are complex symbolic images that call all Jews together and remind us of the power of these days. There are many beautiful images that the Rabbis of the Talmud attach to the shofar and its sounds. In its simplest form, the shofar connects us to our ancient history when we functioned in a tribal system but used the shofar to maintain communication and unity. (On Yom Kippur, the shofar is blown only once, one long blast at the very end of the holiday.)

Before Yom Kippur begins, every Jew is urged to undertake one other action that is not merely preparatory to repentance, but integral to the process: requesting forgiveness from human beings against whom one has committed transgressions. This is necessary in order to wipe the slate of interpersonal relationships clean before the start of the holiday, since only sins human beings and God are addressed during Yom Kippur itself.

A good place to request forgiveness from family members is at the seudah hamafseket, the concluding meal before the Yom Kippur fast. The meal should be substantial, following the talmudic dictum that it is a mitzvah to eat on Erev Yom Kippur, just as it is a mitzvah to fast on Yom Kippur itself. The meal begins with the traditional hamotzi blessing over a challah); because Yom Kippur has not actually started yet when the meal is eaten, there is no Kiddush (sanctification over wine) recited.

After the meal, candles are lit to usher in Yom Kippur. Then the Shehecheyanu-blessing, thanking God for enabling us to reach this season, is recited and the fast begins. Many parents bless their children with the priestly blessing before leaving for the Kol Nidre service with which the holiday begins, and people wish each other “an easy fast.”